Social Security by Choice: The Experience of Three Texas Counties

No. 765

Thursday, April 12, 2012 - National Center for Policy Analysis | NCPA

by Merrill Matthews

Stock market volatility remains one of the primary objections to switching

from the current pay-as-you-go method of funding Social Security benefits to a

system of prefunded personal retirement accounts. However, three Texas

counties that opted out of Social Security 30 years ago have solved the risk

problem.

Galveston County opted out of Social Security in 1981, and Matagorda and

Brazoria counties followed suit in 1982. County employees have since seen

their retirement savings grow every year, including during the recent

recession. Today, county workers retire with more money, and have better

supplemental benefits in case of disability or an early death. Moreover,

the counties face no long-term unfunded pension liabilities.

If state and local governments — and Congress — are really looking for a

path to long-term sustainable entitlement reform, they might consider what is

known as the gAlternate Plan.h

The Alternate Plan. The Alternate Plan does not follow

the traditional defined-benefit or defined-contribution model. Rather,

employee and employer retirement contributions are pooled and actively managed

by a financial planner — in this case, First Financial Benefits, Inc., of

Houston, which both originated the plan and has managed it since inception.

Like Social Security, employees contribute 6.2 percent of their income, with

the county matching the contribution (Galveston has chosen to provide a

slightly larger share). Once the county makes its contribution, its

financial obligation is done. As a result, there are no long-term

unfunded liabilities.

The Banking Model. Unlike a traditional IRA or 401(k)

plan, where account holders can actively manage their investments, the

contributions are pooled, like bank deposits to a savings account, and

top-rated financial institutions bid on the money.

Those institutions guarantee a base interest rate — usually about 3.75

percent — which can increase if the market does well. Over the last

decade, the accounts have earned between 3.75 percent and 5.75 percent every

year, with an average of around 5 percent. The 1990s often saw even

higher interest rates, 6.5 percent to 7 percent. Thus, when the market

goes up, employees make more; but when the market goes down, employees still

make something, virtually eliminating the problem of workers deciding not to

retire because of major drop in the market.

A Real Alternative to Social Security. Social Security is not

just a retirement fund. It is social insurance that provides a death

benefit, survivorsf insurance and a disability benefit. When financial

planner Rick Gornto devised the Alternate Plan for Galveston County he wanted

it to be a complete substitute for Social Security. Thus, part of the

employer contribution provides a term life insurance policy, which pays four

times the employeefs salary tax free, up to a maximum of $215,000. Thatfs

nearly 850 times Social Securityfs death benefit of $255.

If a worker participating in Social Security dies before retirement, he

loses his contribution (though part of that money might go to surviving minor

children or a spouse who never worked). Workers in the Alternate Plan own

their account, so the entire account belongs to the estate. There is also

a disability benefit that pays immediately upon injury, rather than Social

Securityfs six month wait, plus other restrictions.

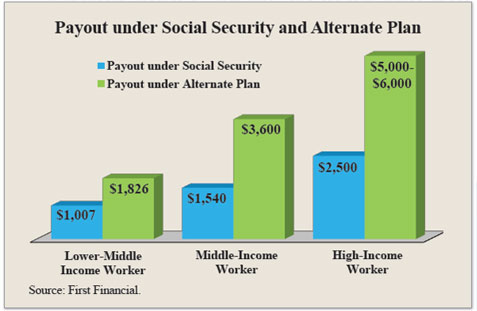

More Retirement Income. Alternate Plan retirees do

much better than those who retire under Social Security. According to

First Financialfs calculations, based on 40 years of contributions [see the

figure]:

- A lower-middle income worker making about $26,000 at retirement would get

about $1,007 a month under Social Security, but $1,826 under the Alternate

Plan.

- A middle-income worker making $51,200 would get about $1,540 monthly from

Social Security, but $3,600 from the Alternate Plan.

- And a high-income worker who maxed out on his Social Security

contribution every year would receive about $2,500 a month from Social

Security compared to $5,000 to $6,000 a month from the Alternate Plan.

It is evident that higher-income workers fare better, relative to

lower-income workers. The reason is that Social Securityfs payout formula

adjusts higher-income workersf benefits down so that low-income workersf

benefits can be adjusted up. The Alternate Plan makes no such transfer

payments. Even so, lower-income workers still do significantly better

than they do under Social Securityfs social insurance model.

It Is Safe and It Works. What the Alternate Plan has

demonstrated over 30 years is that personal retirement accounts work, with many

retirees making more than twice what they would under Social Security. New

county employees who have worked long enough in other jobs to qualify for

Social Security keep those benefits, but they must join the Alternate Plan.

However, the reduced employment time will mean lower returns than if they

had put in a full 30 or 40 years for the county.

A Model for Reform? Roughly 25 percent of public

employees — about 6 million people — are part of state and local government

retirement plans outside of Social Security. Many of those plans are

facing serious unfunded liability problems, just like Social Security.

Those state and local plans do not have to wait for Congress to act — they can

switch to the Alternate Plan immediately. However, state and local plans

currently participating in Social Security are stuck. The Greenspan

Commission, led by soon-to-be Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, closed

that opt-out window in 1983.

The Alternate Plan could also serve as a model for reforming Social

Security. It provides all of the benefits of Social Security while

avoiding the unfunded liabilities that are crippling the program — and the

economy.

A retirement system that is prefunded and safe is not a dream. Three

Texas counties have proven it can work. If states or Congress really

want to address entitlement reform, the Alternate Plan is a good place to

start.

Merrill Matthews is a resident scholar with the Institute for Policy

Innovation in Dallas, Texas.

Copyright © 2012 National Center for Policy Analysis. All rights reserved.